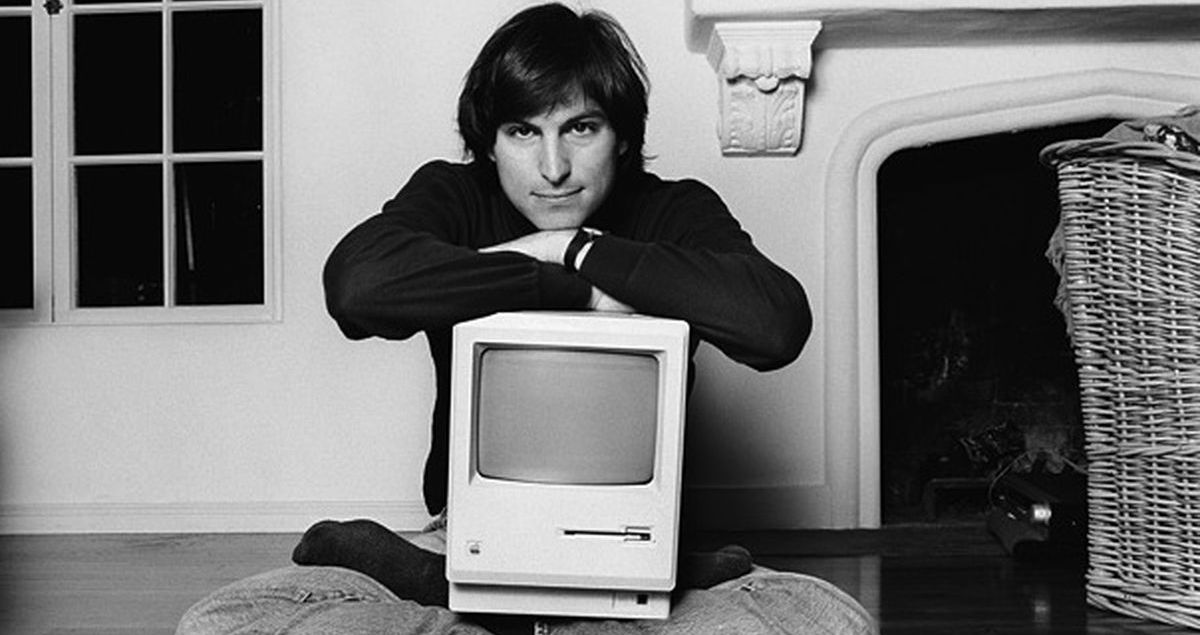

The book, describing the life and career of the current CEO of Apple, Tim Cook, will be published in a few days. Its author, Leander Kahney, shared excerpts from it with the magazine Cult of Mac. In his work, he dealt, among other things, with Cook's predecessor, Steve Jobs - today's sample describes how Jobs was inspired in distant Japan when starting the Macintosh factory.

Inspiration from Japan

Steve Jobs has always been fascinated by automated factories. He first encountered this type of enterprise on a trip to Japan in 1983. At the time, Apple had just produced its floppy disk called the Twiggy, and when Jobs visited the factory in San Jose, he was unpleasantly surprised by the high rate of production errors - more than half produced diskettes were unusable.

Jobs could either lay off most employees or look elsewhere for production. The alternative was a 3,5-inch drive from Sony, manufactured by a small Japanese supplier called Alps Electronics. The move proved to be the right one, and after forty years, Alps Electronics still serves as part of Apple's supply chain. Steve Jobs met Yasuyuki Hiroso, an engineer at Alps Electronics, at the West Coast Computer Faire. According to Hirose, Jobs was primarily interested in the manufacturing process, and during his tour of the factory, he had countless questions.

In addition to Japanese factories, Jobs was also inspired in America, by Henry Ford himself, who also caused a revolution in industry. Ford cars were assembled in giant factories where production lines divided the production process into several repeatable steps. The result of this innovation was, among other things, the ability to assemble a car in less than one hour.

Perfect automation

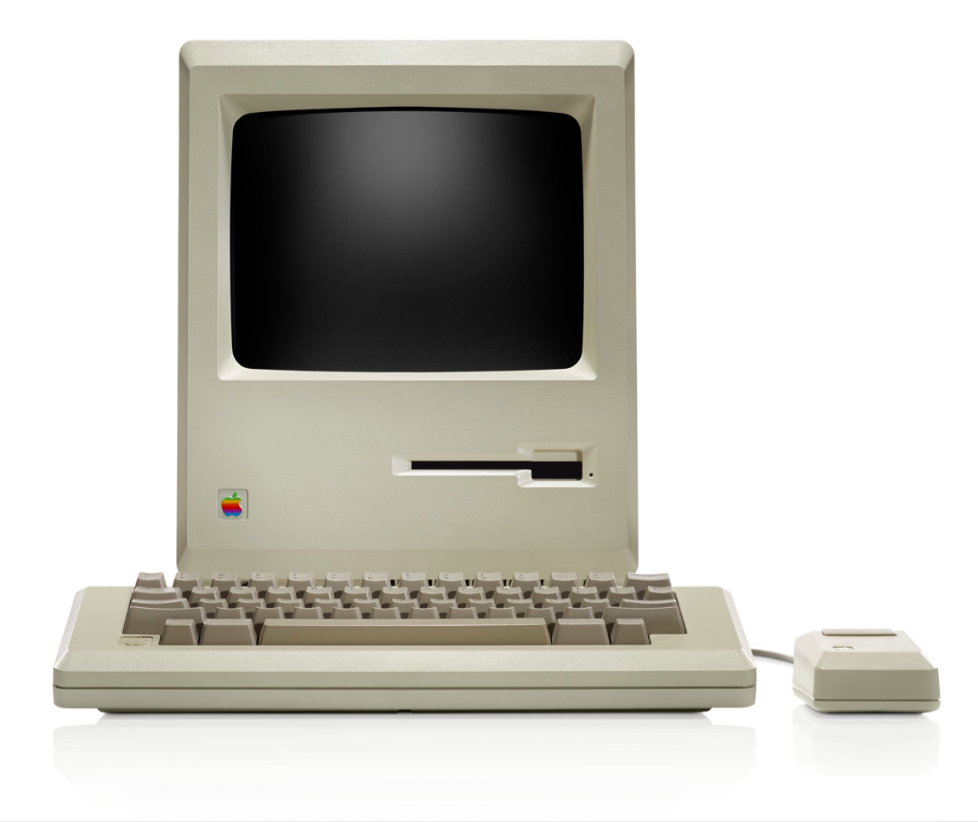

When Apple opened its highly automated factory in Fremont, California in January 1984, it could assemble a complete Macintosh in just 26 minutes. The factory, located on Warm Springs Boulevard, was more than 120 square feet, with the goal of producing up to one million Macintoshes in a single month. If the company had enough parts, a new machine left the production line every twenty-seven seconds. George Irwin, one of the engineers who helped plan the factory, said the target was even reduced to an ambitious thirteen seconds as time went on.

Each of the Macintoshes of the time consisted of eight main components that were easy and quick to put together. Production machines were able to move around the factory where they were lowered from the ceiling on special rails. Workers had twenty-two seconds—sometimes less—to help the machines finish their work before moving on to the next station. Everything was calculated in detail. Apple was also able to ensure that the workers did not have to reach for the necessary components to a distance of more than 33 centimeters. The components were transported to the individual workstations by an automated truck.

In turn, the assembly of computer motherboards was handled by special automated machines that attached circuits and modules to the boards. Apple II and Apple III computers mostly served as terminals responsible for processing the necessary data.

Dispute over color

At first, Steve Jobs insisted that the machines in the factories be painted in the shades that the company logo was proud of at the time. But that wasn't feasible, so factory manager Matt Carter resorted to the usual beige. But Jobs persisted with his characteristic stubbornness until one of the most expensive machines, painted bright blue, stopped working as it should because of the paint. In the end, Carter left - the disputes with Jobs, which also often revolved around absolute trifles, were, according to his own words, very exhausting. Carter was replaced by Debi Coleman, a financial officer who, among other things, won the annual award for the employee who stood by Jobs the most.

But even she did not avoid the dispute about the colors in the factory. This time it was that Steve Jobs requested that the walls of the factory be painted white. Debi argued the pollution, which would occur very soon due to the operation of the factory. Similarly, he insisted on absolute cleanliness in the factory - so that "you can eat off the floor".

Minimum human factor

Very few processes in the factory required the work of human hands. The machines were able to reliably handle more than 90% of the production process, in which employees intervened mostly when it was necessary to repair a defect or replace faulty parts. Tasks such as polishing the Apple logo on computer cases also required human intervention.

The operation also included a test process, referred to as the "burn-in cycle". This consisted of turning each of the machines off and on again every hour for more than twenty-four hours. The goal of this process was to make sure that each of the processors was working as it should. "Other companies just turned on the computer and left it at that," recalls Sam Khoo, who worked on site as a production manager, adding that the mentioned process was able to detect any defective components reliably and, above all, in time.

The Macintosh factory was described by many as the factory of the future, showcasing automation in the purest sense of the word.

Leander Kahney's book Tim Cook: The Genius who took Apple to the Next Level will be published on April 16.

A factory spanning over 120 square feet… Hmmm, I know there is that magical “more than” so it could be like 120k. square feet, but still. It had to be not only a highly automated but also a highly miniaturized factory. :-)