The developer David Barnard, who is behind a number of successful applications, is on your blog focused on describing ten of the most used and sneakiest tactics used by other developers to promote their, often fraudulent, applications. Using ten examples, he shows how easy it is to cheat in the App Store these days and still make a lot of money doing it.

Barnard's list includes classic and relatively well-known practices such as buying fake reviews that move apps up the rankings and help with visibility as well. However, some methods are not so well known and even more dangerous for ordinary users. The list also includes criticism of Apple, which must be aware of the problem, but is not doing anything about it.

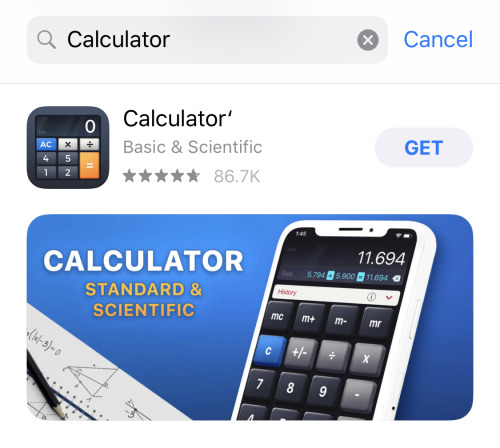

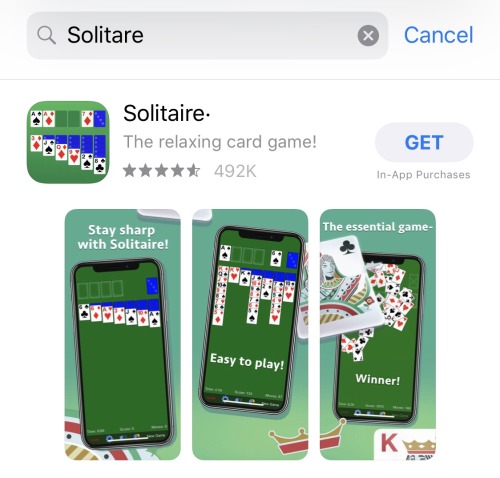

One of the ways to attract as much attention as possible to your application, or to ensure a good position in the search, is to use basic and very frequently searched passwords, such as weather, calculator, solitaire, etc. However, most of these passwords are already taken and Apple does not support duplicate naming several different applications. Developers therefore resort to, for example, adding an extra character to one of the general passwords, such as the already mentioned weather. For example "Weather ◌". The App Store search algorithm then primarily prioritizes search passwords with application names, omitting special characters. An app named "Weather ◌" is thus guaranteed one of the top spots for "Weather" searches.

Another of the unfair practices used by developers is the theft of source data. Speaking of weather, any weather app requires source data to provide to the user. However, this data is expensive and its use requires at least some license fees. So many developers do it by connecting their applications via stolen APIs to someone else's (for example, the default Weather application) and taking data from there. It doesn't cost them a penny, on the contrary, they make money from their application.

Another frequent ailment is aggressive monetization and, at first glance, "dead end" subscription offers, where the button indicating disinterest is hardly visible, or is completely hidden. Of course, there are other fraudulent elements that work with the graphical interface and try to fool the user.

Examples of such behavior are in original article many (including several graphic illustrations). One of the conclusions is that Apple should focus even more on similar behavior, as in many cases there is targeted fraudulent behavior at the expense of users. There is perhaps no need to talk about the fact that the rules of the App Store are being violated.

That's right I used the infusion app and refused to switch to a monthly subscription (I bought it before) until it stopped working and I had to buy it again. I wrote to Apple and nothing.

"On Bernard's List"? It was written by some illiterate…